Blog

From Sketch to Vector Illustration

Hey everyone! Welcome back to Go Media’s Design Blog – where our talented graphic designers share their wisdom with our fellow artists. There has been such a wonderful response on my vector art tutorial “Beautiful Vector Illustration” that I thought I better write another one. If you recall in that tutorial I discussed how to create vector illustrations using photographs as your starting point. A technique of vector illustrating that takes a little bit more skill that I did not cover is starting with a hand drawn sketches. I will focus on that technique of vector illustrating for this tutorial.

For those of you without good sketching ability – please don’t jump ship just yet! I will also discuss a number of tips and techniques to using your pen tool that applies to ALL vector artists – so keep reading. You’ll still learn a thing or two. And who knows – maybe you try to sketch something anyway.

I am going to meander a bit between different sketches, but here is one example of a vector illustration that was based off of a sketch.

This is a design our firm was hired to do for the rock band Mr. Gnome. The theme was straight forward, a gnome with a guitar in a dynamic pose.

The tools you’ll need for this tutorial are:

1. Pencil

2. Paper

3. Scanner

4. Computer (with a monitor)

5. Adobe Illustrator (and Photoshop wouldn’t hurt either)

This tutorial will cover:

1. Sketching – How detailed to get in your sketch?

2. What resolution to scan your sketch.

3. How to set up your Illustrator file.

4. Tips and Techniques to digitally inking your sketch using vector lines.

5. Tips and Techniques to coloring your vector illustration.

Step 1. Sketching.

Ok here we go. Since we will not be using photographs – we’re going to have to rely on our ability to draw. As I mentioned in my tutorial “Comic Book Style Graphic Design” I will not be able to go into the fine details of how to draw here, but I want to try and give you a few tips.

First, I believe that learning how to draw is like learning any other skill. It takes time, practice and it doesn’t hurt if you study a little. So go buy yourself books on drawing, find tutorials online or sign up for classes at your local college. And of course, nothing in the world can replace practice.

This sketching phase of the process should be a fun relaxing part of the process. If you put pressure on yourself you will surely struggle. When I am drawing I try to let go of all expectations. When you sit down to draw tell yourself: “I may draw for the next three hours and may draw nothing good. But I am going to enjoy the process.” Have a pile of paper, a pencil sharpener and an eraser. Always start by sketching as loosely as possible; just work on basic shapes. Get yourself to relax. Turn on some good tunes, have a can of Coke, whatever it takes to get yourself into a good place. I really think this is a big part of getting yourself in the right frame of mind to draw well. It may seem silly – but imagine if you sat down with one sheet of paper, a thirty minute deadline and a rigorous expectation of what you needed to draw. Wow… what pressure! You would be setting yourself up for failure! That’s no fun. So, sit down, relax, let go of any expectations you put on yourself and have some fun.

Also, you need to know that the final sketch will usually be achieved through a process. Many amateur artists don’t truly realize all the “steps” that go into creating a final piece of art like the one I drew. The assumption is that I sat down and in one fell swoop illustrated this final sketch. Frequently there are a lot more steps to this process. Here is a typical process that a professional illustrator might go through to produce a final illustration:

1. Extremely rough “comps” are drawn to show your client what you are intending to draw. Often times there will be several of these so your client has some options. Often times the client will give you feedback on your comps – so you’ll have to modify your composition until they’re happy. Here is a sample of how rough the early “comps” can be:

2. “Studies” are then drawn for a variety of the elements in the image. If, for instance you’ve never drawn a palm tree before you might want to download some pictures of palm trees and sketch them for a while till you get a good handle on how to draw them.

3. The first draft of the final illustration is then done. It always starts with loose light lines to get the composition worked out, then you’ll go over it filling in with “tighter” lines to get your details.

4. Often times some aspect of the illustration looks bad. A professional artist will re-work that part of the illustration on a separate piece of paper until they get it right.

As you can see – this is definitely a process. So, don’t get frustrated if it takes a lot of work to get your final sketch together.

How detailed you get with your sketch is up to you. Personally, I find that it is always easier to decide where I want lines while I am in the sketching phase. So I will get fairly detailed in my drawing before I scan it into the computer. Deciding where to put lines when I’m vectorizing (digitally inking) my sketch is much harder. So I will err on the side of a “tight” sketch (lots of detail) versus a “loose” sketch. Here are two examples of illustrations. This first one is the fairly tight sketch of a demon that I drew for Ozz Fest.

The second sketch is a much more loose drawing:

Lines are not well defined and there is a lot that you would have to make decisions about once you get the drawing into Illustrator. You have to be extremely skilled in your ability to work through a drawing on-the-fly. If you are, you can take a very rough sketch like this and make inking (vectorizing) decisions as you work. I don’t think most people have this ability, so I would recommend that you try to get a little bit more detail into your sketch before you scan it into Illustrator.

While I am endorsing a “tighter” sketch I want to mention the fact that one of the biggest advantage of creating a vector illustration off of a sketch is that the over-all feeling of it is MUCH looser than what you create when you work off of a photo. When, for instance you are working off of a photograph – you are somewhat bound by the natural laws of nature. But in a sketch you can really go over-board with exaggerated features. When you combine these loose exaggerated features of a sketch with the tight clean lines of vector art you really get a wonderfully unique looking illustration. So, don’t be too tight with your drawing! You don’t want to lose your personality.

Step 2. Scanning your Artwork.

HHmm.. not sure why I made this into a whole section of this tutorial. I guess it’s just an important step – you need to get your sketch into your computer. Here are a few tips to scanning your sketch:

1. Make sure to scan your sketch in “photo” mode at 300dpi or higher. You may want to go as high as 600dpi. It really helps to zoom in on your sketch while you’re vectorizing (digitally inking and coloring) it. At this zoomed in state you might be looking at a part of the sketch 300% – 400% bigger than the size you drew it, so you’ll need that extra resolution to see where to put your lines.

2. If your sketch is bigger than your scanner – you’ll have to scan it in pieces and stitch them together in Photoshop. One little tip that helps make this process easier is to make sure that you butt one side of the paper up against the edge of the scanning surface. Scan it, then slide the paper keeping that same side flush up against the edge of the scanning surface. This process insures that your different parts of the sketch are not rotated differently. It is much easier to piece together two images that don’t need to be rotated. Once your sketch pieces are in Photoshop, open one and enlarge the canvas area to make room for the other pieces. Copy-and-Paste the other pieces so that they are all in one image. Set the properties of each layer to “multiply.” This will allow you to see through each layer and more easily line them up. Once you have them all lined up, change the layer properties back to “normal,” flatten the image, and save it as a .jpeg

Step 3. Setting up your Illustrator file.

I like to create 3 layers in Illustrator when vectorizing a sketch. The bottom layer is where I place my sketch. I will lock this layer so I don’t accidentally select it or move it. The middle layer is my color layer. This is where I will fill in my shapes with colors. I will also lock this layer until I get to the coloring part of the process. The top layer is the inks (the lines) of the drawing.

I should take a moment here to mention that you can illustrate vector art without lines. The artwork can be comprised completely of solid shapes with no “line art.” Here is an example of each:

This is a vector illustration without any lines defining the shapes. It simply uses color and value to define the shapes.

This illustration does have lines to separate the shapes.

Whether you choose to make line art or not is up to you, but we WILL be making the line art first on this project.

Step 4. Tips and Techniques to digitally inking your sketch using vector lines.

Ok.. now we get to drawing our vector lines. I don’t have one set style for creating these lines; in fact I have several. I will discuss each. But before I do, I want to discuss our goals. The goals with these lines are that they have character. And by “character” what I mean to say is: “they look cool.” So, how do we make our lines look cool?

For starters, we need our lines to vary in what is known as “weight.” “Weight” of a line basically means how thick or thin your lines are. A lot of weight is thick a little weight is thin. Making your lines vary in weight adds a LOT of character (makes them look cool.)

And where we put this character into the lines is also important. I use three general rules when making a determination of where to put weight:

1. Most important is how close an object is to you. So, if you have a drawing where the super-hero is punching out towards you, the fist would be the closest thing to you. The closer something is to you, the thicker the lines should be. The further away something is – the thinner the lines should be. The city in the background, for instance, should be illustrated with very thin lines. This creates an illusion of depth.

2. The outer-most line of each separate object I will also tend to make a little thicker than the interior lines. This helps define that object apart from the other objects.

3. I will also pay attention to light source. If, for instance, the sun is just over the right shoulder of a character – I might thin that line so much that it ends… there is actually a gap where the line ends then re-starts. The side of the object opposite of the light source will have thicker lines.

4. Finally – I will tend to thicken a line that dead-ends into another line. This is a hard one to explain, so here is a picture:

Now that we have a clear understanding of what kind of lines we’re trying to make… how do we make them?

My first step is usually to outline my object or a portion of the object and then “knock out” the shapes that are inside it. Using my pen tool I will simply find a starting point and start drawing around a shape. If you are not experienced using the pen tool in Illustrator this may be a bit of a frustrating process. Have faith that in time you will get better and faster. It takes time to learn how to best use this tool. Here are a couple of tips:

1. Place your points at the most extreme spots – at the very top of the peak of a curve or the very bottom of a curve.

2. Fewer points will give you a smoother line, so challenge yourself to eliminate points.

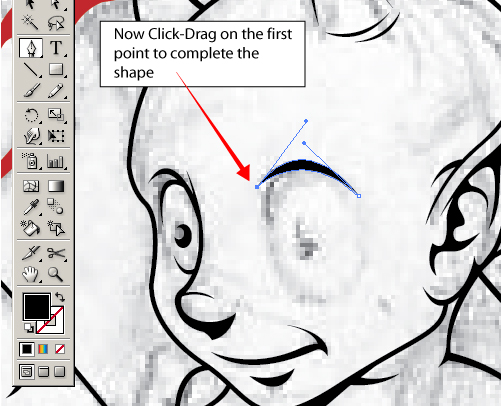

3. If you need to bring a curving line to a sharp turn, click on where the curve will end, click-drag your mouse to create the curve before the sharp turn (don’t worry about the vector line on the far side of the point. When you get the curve before the point where you want it, let up on the button, but before you make your next point – click one time on the point you just made. This will eliminate the bezier handle that runs through the point. When you place your next point, the line from the previous point will come out straight from that point. Here is a little picture sequence of this process. **This is a VERY useful tip. So, if you don’t understand it – read it five more times, study the images below and don’t proceed till you get it. It will be on the S.A.T.!**

Once I have my outline I will simply start drawing the shapes that are inside it that need to be subtracted (or for us old-school designers: “knocked out.”) Be aware that the “lines” you’re creating will be comprised of the outline minus the interior shapes. So, in terms of giving your final lines varying weight, you will have to vary how close your interior shapes are to the outline.

Here is an example of how I will draw an outline, then subtract (or knock-out) the interior with a second shape:

One way to deal with this varying line weight issue is to deal with it in the sketching phase. This way – you don’t have to think about it while vectorizing. You can just follow your sketch lines.

While you are drawing these knock-out shapes you may want to ignore little detail lines that might be hard to draw. If for instance you have some cross-hatching lines that extend from a large black shape – I won’t try to draw them both at the same time. I will start by just drawing the black shape, then will go back and draw the hatch-lines. I can merge these shapes using the Pathfinder tool later if I want to. Here is a sample of that:

Once you have all of your interior shapes in place, you’ll now need to knock them out of your outline. You will do this by

1. Grouping all of the interior shapes.

2. Bringing these grouped interior shapes to the front: Object>Arrange>Bring To Front

3. Selecting both your grouped interior shapes and your outline

4. Clicking on the knock-out (or “subtract”) function of your pathfinder tool.

5. Fill with black! (or whatever color you want your lines.)

Another way to draw lines of varying weight without drawing the inside and then the outside of each line is to just draw a single vector line down the center of your intended line. Then you “stroke” this line with a brush. Specifically you might want to use one of the calligraphy brushes that Illustrator includes.

Here is how using one of these brushes looks when applied to a curving line:

This looks great and is a much easier way to make lines with character – but it is much harder to control where the line is thick and where it’s thin. This is determined by the shape of the brush and the angle of your line. If you have a set of brushes set up at various angles and experiment a bit, you can figure out how to control where the thick and thin parts of your line are, but it takes some work.

If you are using this technique to vectorize (digitally ink) your sketch there is one additional step you have to take. Once you get the line how you want it, you’ll have to: use the Object>Expand Appearance function. This will take your brush stroke and convert it into a solid shape.

You may also experiment making your own brushes in Illustrator. One very useful brush is a simple triangle.

Simply make this triangle shape, select it and then go to the drop-down menu in your brushes window and select “New Brush>New Art Brush. Then draw a curvy line and apply this brush. You will quickly see how useful it will be in inking. Here is a sample of what a triangular brush on your vector path looks like:

I suggest experimenting with brushes like this. I will not reveal all of Go Media’s secrets here – but this should get you started.

Now you have the meticulous job of “inking” your illustration. Depending on how complex your drawing is – this process may take an entire day or more, so settle in and try to enjoy yourself. After all – that’s why we’re here right?

Here is the finished inking I did on this sketch… Pretty sharp if I do say so myself!!

First the pencil sketch:

Now the final inked illustration:

Ok, now to the really fun part – coloring.

Step 5. Tips and Techniques to coloring your vector illustration.

This tutorial is going to cover coloring in Adobe Illustrator. At this point you could also export your line art to Photoshop and color your drawing in it. In fact, most professional coloring you’ll see of illustrations is done in either Photoshop or Painter. Making a vector coloring – as we are in this tutorial is a very different process with a different look and feel to it. In Photoshop for instance, you can much more easily make soft-edged transitions between your various colors. Here in Illustrator your color shapes will have sharp edges.

Now I will make a confession – I don’t think I have a very good sense of color. I think I am a bad colorist. So, hopefully I can give you some tips I use to “fake it.” Remember: “Fake it till you make it!”

Now, you’ll be coloring on your color layer, so lock your inking layer and unlock your color layer.

Usually I will try to pick the colors I’m going to use before I start coloring. I will start with 2-4 main color themes that work well together. For each of these colors I will try to get a range of color values from dark to light. Once I have this palette of colors I try very hard to stick with it. Since I don’t have a good sense of color, I’m afraid to stray too far from a nice color palette once I’ve made one. Here is an example of a color palette I put together:

I will usually assemble my color palettes by opening a Pantone Swatch Library (located in the Swatch window drop-down in the Swatch Libraries drop down). I’ll then see a color I like and grab the entire value range from dark to light of that color.

One “cheat” I use occasionally for finding a good color schemes– is the website: colourlovers.com. It doesn’t give a complete coloring palette and isn’t usually exactly what I’m looking for, but it’s a great resource for inspiration.

In the case of this illustration, he went with a fairly straight-forward coloring scheme. The girl’s skin is flesh color, the skull is grey and the devil-baby is red. For each of these object there is about 3-4 color values; a middle value, one dark color for shadows and one light color for highlights.

While going with a straight-forward coloring scheme is fine, I want to encourage you to really experiment with colors. Explore the space. I got a fever, and the only prescription – is MORE COW BELL… no wait – I mean – MORE COLORS. I think doing a good realistic coloring job is almost passé these days. Using non-traditional colors is the current trend.

To start, lets use this little devil baby sketch that Dave did and start by filling each main shape with a middle value. Here is what the baby looks like with each of his primary shapes filled with the middle-value. You’ll notice the back of the tail is dark. We obviously decided that we were going to have a light source to the upper left. This would place the tail in a shadow.

When I say “We filled each main shape..” what I mean specifically is that we stole the line art and used the vector lines that were already drawn to fill the main shapes.

In order to do this you need to make sure you’ve used your Pathfinder tool to subtract (knock-out) and consolidate all your line art into one complete path, then you will:

1. Unlock your inking layer (if it isn’t already)

2. Select your Inks (lines)

3. Edit>Copy

4. Switch to your color layer (I’ll even re-lock my inking layer)

5. Edit>Paste In Front – this will drop a copy of the inks into the coloring layer in the exact same location that it was taken from – so it lines up perfectly.

6. Select the line art and then Object>Compound Path>Release. This will break all of these shapes back up into their own pieces of art. You can then delete the outline and simply deal with the fill shapes. By selecting them you can fill them with the appropriate color.

Using this technique will save you a lot of time. Here is the single-color initial fill of the devil-baby:

If you are not familiar with the Pathfinder tool in Illustrator, let me just say: please take the time to explore this tool. It is indispensable. I use it constantly.

Once the main color fill is in place, we can start adding shadows and highlights. Since your highlights and shadows will be contained within the area we’ve already established with our fill, you really only need to draw the line that will distinguish the barrier between your middle value and shadow.

In this first image you can see where I drew the dark red shape to define the shadow area. I only concerned myself with where my shape intersected with the red fill of the devil baby’s body.

I then need to make a copy of the devil-baby’s fill shape so I won’t lose it when I use the pathfinder tool. I use the Copy and Paste-In-Front function to create two duplicate shapes that are directly on top of one another. Then I select the main fill shape and the shadow shape as well.

Then, using the Pathfinder tool use the overlap Pathfinder tool. I’m not sure what the technical term is for this function, but it basically takes two shapes and removes any parts of them that do not over-lap. Here’s a pic:

I will go through and use this technique to define each of my shadows, bright spots and any other little details I would like to add.

So there you have it. An insight into my mind as I go from sketch to vector illustration. This is how I do it, but every illustrator has a different technique. So use this article/tutorial as a guide to help you establish your own technique. I hope you learned something useful!

Lastly, make sure to check out our Arsenal Membership, which hooks you up with our huge product library for only $15 per month. Yes, seriously.