Blog

Switch It Up

CG artist and filmmaker John Robson on developing the skillset today’s studios want.

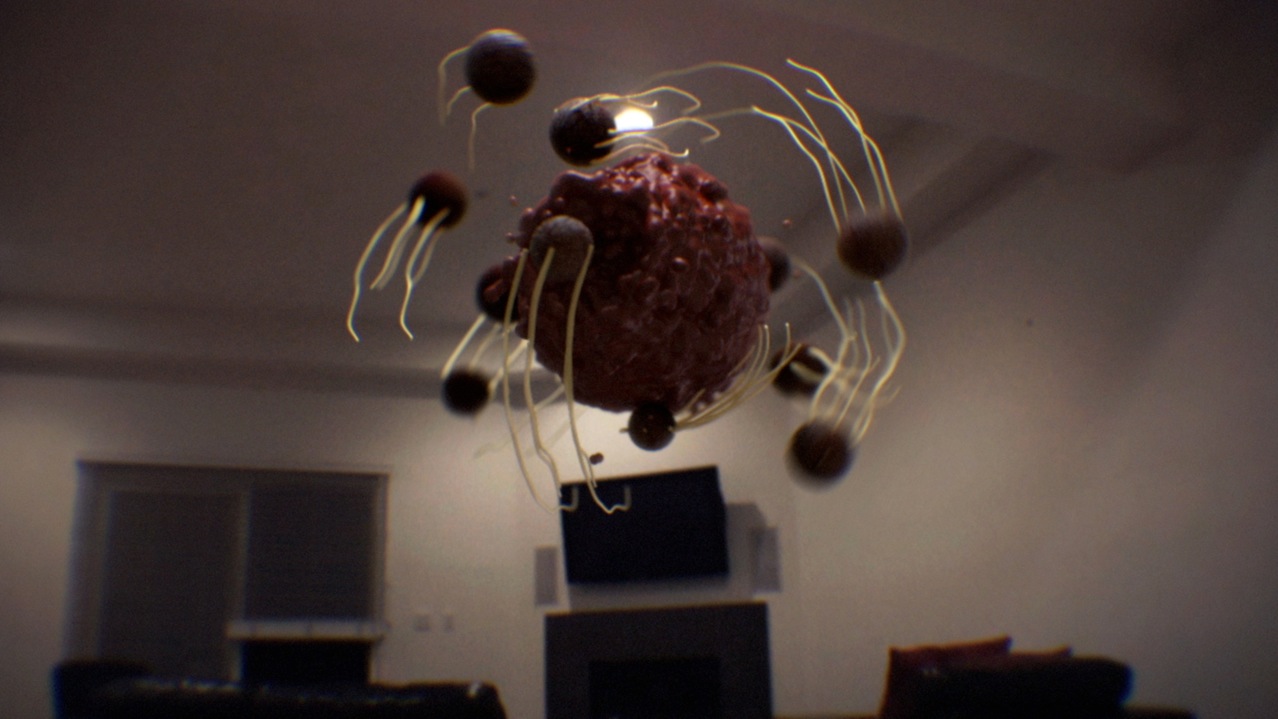

Faced with the assignment to make a short film based on the question, “What’s the best thing you’ve ever eaten?” Los Angeles-based CG artist John Robson opted to put the question to a friend’s three-year-old son and film the kid’s response. The result is Supper Time! from John Robson on Vimeo. And, well, let’s just say you’ll never look at spaghetti the same way again.

Supper Time! from John Robson on Vimeo.

In addition to filming and directing Supper Time! Robson created all of the VFX using Maxon’s Cinema 4D and Next Limit’s RealFlow, and he did it all in one week. “MoGraph allowed me to create new ideas without being bogged down by technicalities and slow processing times,” he explains. “So I was able to work almost as fast as I could think.” (See more of Robson’s work here.)

A freelance designer and CG artist who works for a variety of well-known houses such as Blind, Troika, Mirada and Royale, Robson made the film as part of Frame Society. Organized by Blind creative directors Chris Do and Greg Gunn, Frame Society is basically a group of filmmakers, writers, animators, directors and other creative people who meet after hours to share ideas and talk about everything from camera work and lighting to VFX. “Almost everyone in the group has been in the industry a long time by work or by hobby,” Robson explains. “So we understand how to tell a story just because we’re living in that world.”

Evolving With the Industry

Like many creative people, Robson didn’t plan the career he is currently pursuing. Instead, cinematography studies at the University of California-Santa Barbara led to curiosity about how to create special effects for film, and pretty soon he was learning Final Cut Pro and After Effects. By 2003, Robson got his first job doing motion graphics. He taught himself how to use Autodesk’s Maya, and that’s where his real education began. “I learned everything on the job, so that was really college for me,” he recalls.

Describing himself as more comfortable following a creative path rather than a technical one, Robson says his skills took him down yet another road when, at the suggestion of other artists he knew, he taught himself how to use Cinema 4D. “All the big teams were using Maya, but when MoGraph came out it completely revolutionized my workflow and that of the other artists, too,” he says. “Suddenly, we could pretty much do anything in real time and experiment on the fly, sort of like being in the kitchen with unlimited ingredients.”

As a freelancer, Robson is well aware that in order to stay busy, he must evolve with the industry. Over the years, he’s watched as artists who have insisted on specializing in just one area either create a reasonable niche for themselves, or wind up without enough work. So, knowing that studios are always looking for artists who understand a variety of software, he splits his time between directing his own projects, design, 3D and 2D work, and compositing. “No matter what job I’m on, I’m almost always using C4D, especially MoGraph,” he says.

Meeting the Need

Robson’s remembers really putting his C4D skills to the test as a freelancer working on a project for Mirada. Finding himself waiting for assets from the rest of the team, he decided to play around and see what he could create in Cinema 4D. “I was working and one of the art directors came by and couldn’t believe I had created what I had in one day, so they asked me to do another and another, and soon we had a huge Cinema farm going,” he says, explaining that Mirada often uses C4D, Maya and Houdini in combination.

For this particular Mirada project, Robson and others on the team were asked to create photo-real popcorn and Coke in stereoscopic 3D for Carmichael Theaters. Robson was the C4D lead on the job, and the team used a combination of C4D, MoDynamics, RealFlow, Houdini, NUKE and Next Limit Technology’s Maxwell Render engine. “Mirada brought me in on the project because they knew Cinema had the power and efficient dynamics for the project, but it was before C4D R13, so I had to build my own stereo rig,” he says.

With the help of fellow artist Casey Hupke, Robson created the popcorn by emitting Thinking Particles from above the screen and linking them to a MoGraph matrix object. “This bridged the gap between modules and utilized the best and most efficient features for the job,” he explains. Rigid body MoDynamics were added to all of the pieces, so the popcorn fell, accumulated in a funnel just above camera, and then spilled into the tank. Coke appeared to pour over ice and fill the screen thanks to RealFlow.

Pursuing a Passion

Even when he’s crunched by deadlines, Robson always makes sure he finds time to do some personal work. Recently he finished a short film called Infinite Loop,which is based on the idea of what it would be like to be stuck in kind of hall of mirrors. “It all starts with a guy at a party who starts messing around and plugs a cable into a TV,” says Robson, who directed the film and created all of the VFX using Cinema 4D and After Effects.

“The film kind of shows you what would happen if you pointed a video camera at its own image,” Robson says, adding that although he had an idea of what the footage would look like when it was shot, everything changed when it came time to animate. “I was coming up with all kinds of new ideas in post,” he continues.

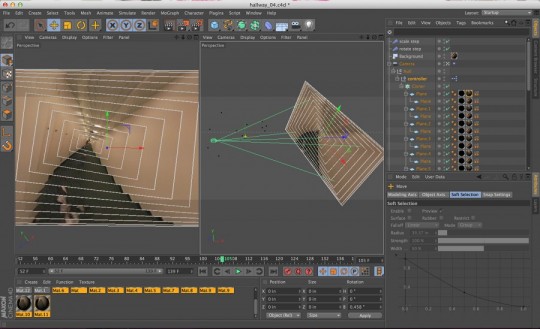

“I camera tracked some shots and brought data into Cinema and created expression that I applied to a MoGraph cloner with a step effector to create a delayed process.” The goal was to create a retro feel, something simulating what would happen if you attached a cable from a video camera to a TV screen, “but didn’t want that screen to be too intrusive visually,” he says.

For the hallway tunnel shot, Robson tracked the plate in SynthEyes and created an expression that compensated for the XY position and Z rotation of the camera while applying the values inversely to a step effector’s parameters. “This replicated the effect that a camera has when it views a screen with its own image on it,” he says. The step effector also scaled down each concurrent screen to create a forced perspective of what looks like a long tunnel, but is virtually flat. Each clone’s video footage had to be manually offset to simulate the delay of transmission between iterations of the screen down the tunnel.

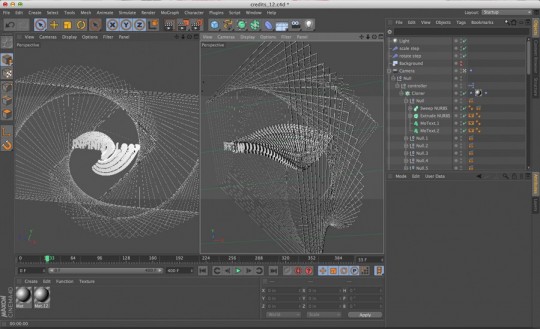

The end credits were made by applying a step effector to a cloner object and creating iterations of the type and border that were rotated, scaled, and positioned over the course of several clones to create a spiraling tunnel effect that gradually shifted from clone to clone. “I created a series of user data sliders driven by Espresso that influenced the intensity of the values of the step effector and allowed a simpler control for randomizing movement,” Robson recalls. Each clone was rendered out with a different object buffer so he could randomize opacity for each object buffer in After Effects to create a flicker effect.

“I’m really proud of how it turned out,” says Robson, pointing out the film’s “urban legend-like spin” in which pointing a camera at its own image means the party guy gets immediately transported into the TV, a fate from which he cannot escape. “All through the film you see him running away, thinking he’s outsmarted technology, but in the end he’s still stuck in the TV and his friends forget about him.” Interestingly, after the screening of the film, some people wondered aloud whether the film’s subtext had something to do with a fear of technology. For Robson, though, it would seem the opposite is true.